News . Feature Stories . Making work from Mother Nature's bounty

News

November 15, 2016

Making work from Mother Nature's bounty

Bees, birds and bark beckon Kautenburger's eye

Photo by Robert Muller/CIA. See additional photos below.

By Betsy O’Connell

A honeybee’s wings beat about 200 times each second. That’s about the speed of Kevin Kautenburger’s thoughts, too.

The bees’ wing strokes produce their distinctive buzz; Kautenburger’s whirlwind energy emits a trail of art, natural history and passion for learning.

Kautenburger, an associate professor at the Cleveland Institute of Art, teaches the Foundation Design course as well as Environment, Art and Engaged Practice at the Cleveland Institute of Art. The latter is a collaboration between CIA and the Cleveland Metroparks, where he and his students explore the intersections of art and nature.

In many ways, Kautenburger is most at home among nature’s trappings, whether at the park or at his home in Berea, where beehives and live poultry share the land. Nature supplies mysteries. Kautenburger’s artistic side provides a vehicle for exploration, mostly through the development of three-dimensional forms.

In the classroom, Kautenburger stokes that curiosity in others. CIA Illustration major Jarod Perry-Richardson is in Kautenberger’s Engaged Practice class, and is focusing his attention on a rotted log by a stream. He has made molds of it using cement mixed with soil from the site, and will place these man-made “fossils” in the habitat to mimic an archaeological find.

Perry-Richardson also has taken photos and written poetry to incorporate into his project. “I took this class because I wanted to branch out in my art,” he says. “It’s a good place to think and absorb the natural world.’’

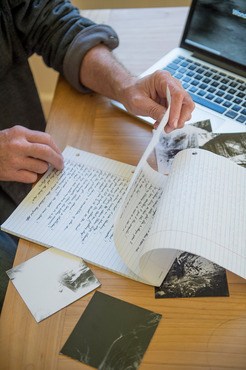

Kautenburger is a 2016 Creative Workforce Fellow through the Community Partnership for Arts and Culture, supported by Cuyahoga County taxpayers. As part of that, he is creating a book project he calls Wonder: Connections to Nature. He invites members of the public to visit all 18 Metroparks reservations with him and participate in a writing and photography exercise that involves the use of pinhole cameras.

“I’m interested in this idea of peripheral vision and interesting ambiguity, which I see in pinhole photos,’’ he says. “The struggle to take images while having very little control helps me to see, regardless of the image quality.”

Each Metroparks reservation will have two pages in the book with an image and text. Kautenburger is still working out how to pick what he will use. He will play with the aesthetic of the type —perhaps embossing it over the image. “This is new territory for me,’’ he noted. “I’m not a writer. I don’t work with text. I’m not a public artist.’’

Woodworking is a more familiar territory. Kautenburger’s woodshop is in an outbuilding behind his home, just past the pen that houses turkeys Ben Franklin and Marie Curie, and through the yard where the family’s chickens roam.

Kautenburger trained in school as a ceramicist. He had a studio in Philadelphia near a woodworker, and learned some of his skills there. But he is largely self taught, and first honed his wood skills making beehives. “I got into beekeeping because of the seemingly mystical tools, like the smoker and bee suits,’’ he says. The objects themselves attracted him. “I’m interested in the potential poetry of things.’’

Wood sculptures occupy studio space, but canvas works compete more often for display. A sewing machine and related items occupy one side of his studio worktable.

Kautenburger likes the quiet process of working with fabric. “Maybe I’m thinking about my mom. I remember hearing the sewing machine at night when I was young,’’ he says. “I like to be able to fold up my work.’’ He picks up a recent work, which looks like two butterfly nets connected in the middle by a long canvas tube. “I like the softness of the fabric.’’

A canvas structure on one studio wall reveals itself on closer inspection as a pup tent, housing a naturalist’s discoveries. He plans to make a series of them, each holding natural-history information, he says.

Longtime CIA faculty member Barbara Stanczak has been Kautenburger’s friend from his early days at the college, where he began teaching in 2001. “What attracts me personally most to Kevin is his humility, a very rare quality, especially knowing the ego of most artists,” she says. “His simple, honest, uncomplicated character invites cooperation. Kevin is totally unpretentious. What you see is what you get.”

Stanczak sees Kautenburger’s work as a natural outgrowth of his character.

“He explores nature with humble curiosity, even reverence. His material choices and preferences are from nature, and they give dignity and beauty even to mud, leaves or bugs,” she says. “You can find Kevin talking enthusiastically about his chickens, turkey or bees, recording with curiosity and awareness fine detail in their growth. This awareness feeds his visual choices and becomes transformed into sensitive handling of the materials at hand. I find no separation between Kevin the individual and Kevin’s work. One reflects intuitively the other.”

Latest Headlines view all

-

April 02, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art students partner with Progressive Art Collection to exhibit Ready, Set, Relay! -

March 04, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art announces Curlee Raven Holton Inclusion Scholar Program -

November 06, 2023

Collision of art and artificial intelligence creates murky waters for artists, curators and educators

Questions?

For more information about this or other CIA news, contact us here.

Social Feed