News . Feature Stories . Visiting Artist: Michael Janis

News

January 09, 2017

Visiting Artist: Michael Janis

'I like that I can almost zone out and lose myself as I work'

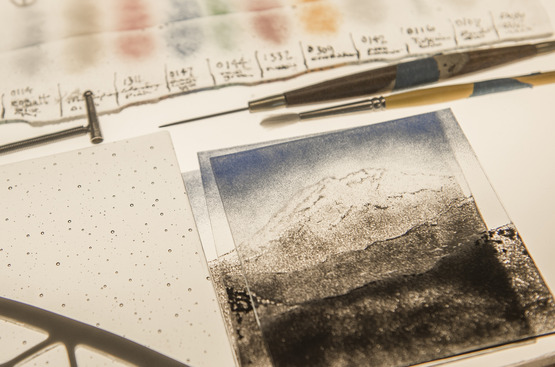

Photo by Rob Muller/CIA. See a slideshow of the artist's work below.

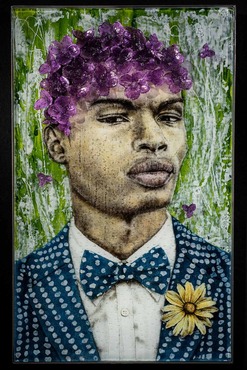

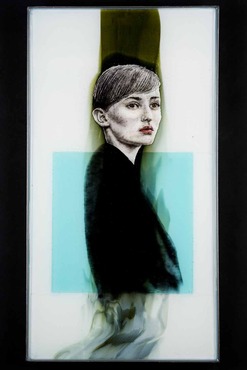

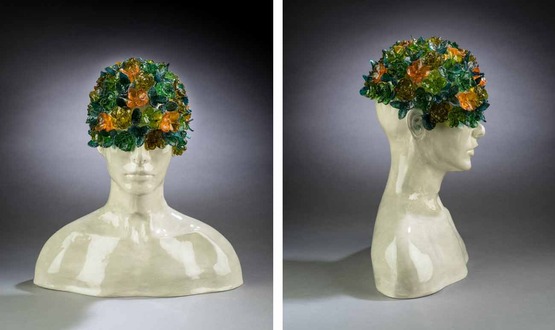

Glass artist Michael Janis, co-director of the Washington Glass School in Mount Rainier, Md., specializes in sgraffito, a technique that uses crushed glass powder as a drawing medium. A 1983 graduate of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), Janis started his professional life as an architect, working first in Chicago and then moving with his wife to Australia. When the couple returned to the United States in 2003, Janis decided to dive into the art career he’d always wanted, and began a serious practice in glass.

Janis has an extensive list of public commissions, including casting of glass doors for the Adams Building at the Library of Congress, and a sculpture in the lobby of Washington DC’s Palomar Hotel — which the local edition of the satirical newspaper The Onion reviewed as the “(expletive) creepiest windows ever.”

Among publications that have featured his work are the Washington Post and American Craft magazine. He has objects in three exhibitions during the first half of 2017, including Mindful: Exploring Mental Health Through Art at the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art January 28 through April 16.

Janis visited the Glass Department at the Cleveland Institute of Art in November 2016. He also answered a few questions about his work and his decision to switch careers mid-stream.

Did you come away with any impressions about CIA after your visit?

I come from a background of an architecture and engineering school. So I’m rather jealous of how much is provided for the students — the facilities and equipment are incredible. I hope the students realize how lucky they are. But once you get used to that level of resources, how do you replicate it after [you leave] university?

The students are going to have to create networks that allow them to do work. They will need to find the wood artists, the ceramic artists, the glass artists and establish working relationships that could allow access to facilities and tools — and advice.

What’s different now than when you started your career as an architect?

The days of having a one job career are over. Even the notion of the safe government job doesn’t exist anymore. As the idea of secure jobs continues to disappear it’s better for one to be flexible. If you’re trained well and open to options, it’s good to be the jack-of-all-trades, with a broad knowledge base — know a little bit about everything. And you have to be a businessperson and entrepreneur, thinking in terms of expenses, R&D, fabrication time and always be marketing. There’s a lot to juggle.

What kind of art did you like to do as a kid?

I liked to draw, I loved drawing. As a young kid, you could shut me up for hours by putting a piece of blank paper in front of me and giving me a pen. It didn’t even have to be paper. If was lucky enough to have a marker, I’d go nuts. I drew constantly.

But as I understand it, your parents were not in favor of you becoming an artist.

For them, the goal was to have all their kids become doctors. A doctor was the secure and prestigious profession they dreamed of. I said I’d like to be an artist. They kind of looked at each other and then looked back at me and said, “That’s not going to happen.” They had very conservative backgrounds and aspirations, with job security being very important. My mother worked as a machine operator for the Avon products bottling factory and my father worked in office services for the publisher of Chicago’s telephone directory, and they wanted something better for their children. Saying that I want to become an artist was, to them, as though I was saying “I want to be unemployed and starving.” Art was nice, but they didn’t think I could make a living with it.

Architecture seemed like a good compromise. Did you enjoy being an architect?

I really like working in design. I like thinking through the process of how one would build something. At architecture school, the students couldn’t design with bricks until they understood how they were made; how they worked stacked a wall; how to turn the corner with the masonry. The curriculum was that you would have to know the medium before you could start expressing and exploring design. IIT’s Bauhaus background instilled in me a love of combining practical skills together with problem solving. I loved the architecture projects I worked on that allowed for experimentation and allowed for artistic integration.

However, being an architect wasn’t like [TV sitcom architect] Mike Brady designing extravagant powder-puff buildings. As an architect, you are mostly doing budgets, schedules and reports. Design seems to be the smallest part of any project. Mostly I was writing up reports as to why I specified one product or process over another. Everything was budget focused, which I think is an important thing, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do as an architect.

When I was an architect in Australia I began using glass as a design element, and exploring that medium renewed my desire to be an artist.

What kind of artist would you have been if you hadn’t been an architect first?

I don’t think I was even focused [at the time] enough to know what I wanted to do. I know I really responded to the figurative works by [photorealist painter] Richard Estes and as an architecture student, I made presentation renderings in his style. I also loved Dadaism and Surrealists, where unexpected combinations create new worlds.

My career as an architect gave me a strong sense of discipline and a different focus. I pushed away from my architecture background when I first started working in art, but then I realized that instead, I should embrace my history. And I think I started to find my voice once I embraced my background.

How did your wife react when you said you wanted to trade in your architecture career for art?

My wife was also an architect, and she changed her career while we were in Australia. I reasoned that I had supported her while she got her MBA, and if we were making big changes and moving back to the US, I wanted to make big changes and work with glass. She said, “If you think you can make a go of it, sure.”

And were you sure you could?

Oh, I had no idea. I was going to the great unknown. If I’d fail, I’d fail - but I didn’t want to stay being an architect.

I was first glassblowing at a studio in Baltimore, which was quite a distance from where we were living after we returned stateside. The commute killed me; I had to find a studio in DC. That’s when I found the [Washington] Glass School. I walked into the Glass School and I really was taken by their approach to glass and art. The Washington Glass School was - and still is- a hands-on education center for glass art. The school is about kiln-formed glass, as well as having classes in other media like steel and concrete. I liked how they encouraged the unusual and experimentation. How glass was art, it was craft, it was to be sculpture, it was to be architectural. I wanted to be part of the school, but I was worried about how to pay for many classes without a job. After taking a couple classes, I offered to work in exchange for the classes as the studio assistant. I was shop monkey there for a while, and my architecture background came into play as the studio part of Washington Glass School sought out larger project commissions. In 2005, I became a co-director, and it felt like home.

Let’s talk about the process of drawing in glass powder for a minute. Is it as painstaking as it looks?

It’s a slow process. I use finely ground glass — frit — the consistency of powdered sugar as the basis of my drawings. Using fine mesh sifters like enamellists use, the glass frit gets sifted onto the surface of flat glass that is on top of a lightbox to show the density of the applied powder. Using an X-acto knife, I push around the powder, clearing some areas and maneuvering the frit into lines and shaded areas. I also use rubber-tipped tools and brushes to move the glass. It’s not so much drawing as it is pushing around loose powder. If you sneeze, it’ll blow away. If you bump the edge of the light box, it’ll shift. And if someone has a fan on in the studio, you need to make sure the air doesn’t blow your work away you walk your work to a kiln to fire into the glass. Speaking from experience here.

I like that it’s a slow, thoughtful process. I like that I can almost zone out and lose myself as I work. This is where my obsessive nature comes in. Maybe work larger. Or smaller. Or change the concept midstream. I let the piece evolve as the image develops. The slow process lets me constantly use the skills I’ve built as an artist, the ones that I continually work on and internalize to the point of intuition. Ultimately, the work isn’t just by me, its of me.

Latest Headlines view all

-

April 24, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art welcomes alum Omari Souza as 2024 Commencement speaker -

April 02, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art students partner with Progressive Art Collection to exhibit Ready, Set, Relay! -

March 04, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art announces Curlee Raven Holton Inclusion Scholar Program

Questions?

For more information about this or other CIA news, contact us here.

Social Feed