News . Feature Stories . Fiorelli designs new beginning after 32 years at CIA

News

May 13, 2016

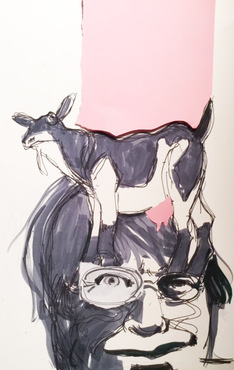

Fiorelli designs new beginning after 32 years at CIA

One-of-a-kind Foundation prof influenced a generation of artists

Photo: Robert Muller/CIA

By Karen Sandstrom

There’s nobody like Richard Fiorelli.

No one acts quite like Fiorelli, teaches like him or thinks the way he does. His mind makes split-second associations with words and names. He sees a broken chair in a library and asks permission to adopt it. Where others might figure out how to fix it, Fiorelli wants to think about what else could be done with it.

“I will play with it to tease out some unforeseen possibilities,” he says. “Dynamic. Gestural. A first step. Open-ended play.”

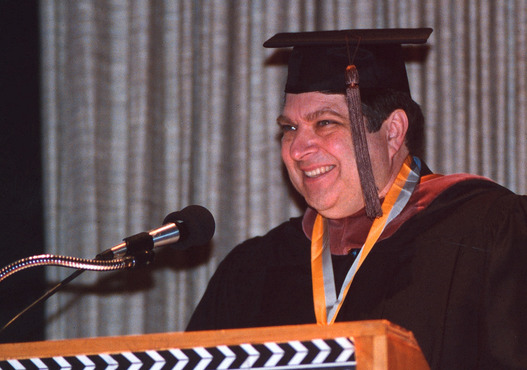

This month, Fiorelli is retiring after 32 years of teaching design and drawing in CIA’s Foundation department. It caps a nearly lifelong connection with the college. And it’s the end of an era of Fiorelli’s storied influence on decades of students, including some of CIA’s most accomplished alumni.

But retirement isn’t likely to end what some call “the cult of Fiorelli.” That will go through his 300-member Facebook fan page (started by former students), in stories swapped among friends, and in how artists and designers still bring “Fio” lessons to their daily work lives.

There is an “assumed way of knowing how to teach students how to approach art,” says 2016 Ceramics graduate Meghan Calvert. But Fiorelli challenges the assumption. Calvert says Fiorelli exhibits “a natural reject of the first thought that comes to mind.”

“He’s not first generation or third generation. He’s like the fiftieth generation of a thought,” she says.

If you ask Fiorelli himself, he’ll tell you that his uncommon way of looking at things goes back to the beginning. As a kid, he struggled with academics, thanks to what would much later be called a learning disability. But he liked art and he could immediately hear wordplay.

“In elementary school, I did a very long drawing on shelf paper of the Flintstones’ Bedrock Quarry,” Fiorelli says. “To promote literacy, I wrote ‘Fred RED, why don't you?’ It was an intentional error, but my mom was convinced that I could not spell the word correctly.

“I was just considered dumb, that’s a fact,” he says. Now he knows that while his neurological paths were “miswired from birth,” that gave him a creative edge.

“Somehow I flipped that negative into a positive.”

Fiorelli attended classes for children at CIA. When it came to college, the institute seemed like a natural choice. He was accepted on probation, thanks to low test scores from high school, and had to take an adult English class with non-native speakers.

By fall of 1969 he was on his way to earning a BFA degree with a painting major and a sculpture minor. Upon graduation, he won the Nancy Dunn Scholarship — the equivalent of what is now the traveling scholarship.

He did a stint as a graphic designer before earning his master’s degree in sculpture at the University of Syracuse.

Among Fiorelli’s claims to fame as a struggling graduate student was a brief job making custom bases for a series of Anthony Caro sculptures that were going on view at Syracuse. He was at work one day when the esteemed art critic Clement Greenberg came in to examine the bases. Fiorelli walked around with Greenberg, taking notes on changes to the bases as ordered by Greenberg — at Caro’s request.

“Finally, I said, ‘Mr. Greenberg, I have to ask you, what gives you the right to rearrange an artist’s sculpture?’ He says, ‘I’m a hired gun.’ “

By the way, Fiorelli adds: Greenberg’s judgment was “perfect, in my opinion.”

Fiorelli lived in Boston for a while in the late ’70s, taught summer classes at CIA, and then followed a girlfriend to Baltimore. There, out on the street in one of the highest-crime cities in America at the time, he heard gunshots and saw a man run by him. When the police came, Fiorelli offered a verbal description, then returned the next day with a sketch of the suspect.

A few days later, the Baltimore homicide unit called and offered him work as a sketch artist. He made $200 a drawing — enough to sustain him at the time — but the work was a grind. He recalls a witness breaking down in tears as Fiorelli sketched his lover’s killer; the survivor had never had the chance to tell his partner he loved him.

There was the shopkeeper wracked with remorse after selling a knife to a customer who had come in chanting that he was going to kill a woman — then did.

And this was the ‘80s, when teenagers started killing each other over designer tennis shoes.

“I started seeing that kind of stuff and realizing it’s not going to stop,” Fiorelli says. By the time he was offered a job teaching in the CIA Foundation department, he was ready to move on. “I saw teaching as a more constructive, positive venture,” he says.

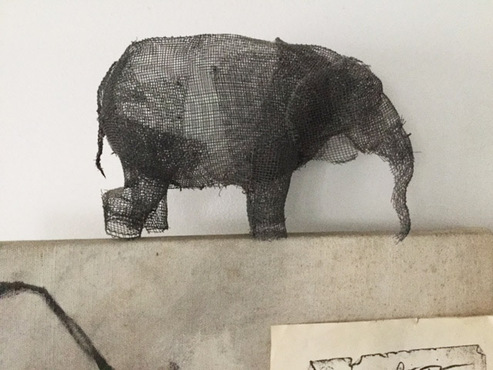

Over the years, his three-dimensional design classes became known for their wacky assignments: create a hat that allows you to pass a Ping-Pong ball to someone without touching the ball; make a shared headpiece for two people having a conversation; design a vessel that allows you to drink water from it without holding it. The results weren’t always pretty, but the point was mind expansion. Think beyond the obvious. Turn the puzzle upside-down.

Fiorelli praised ingenious solutions. Struggling students got gently coached or briskly challenged, depending on what they needed.

“Richard Fiorelli was the only teacher at CIA who ever made me cry during a critique — not by yelling, but simply by calling me out on my half-ass project conceptualization and execution,” said animator and entrepreneur Kevin Geiger ’89.

Pure slackers occasionally saw the Fiorelli anger flare.

But Fiorelli has mellowed. He dates certain changes in perspective to 1993, when he collapsed in the classroom and was rushed to Mt. Sinai Medical Center. During the emergency room exam, his heart stopped. For a moment, he was dead.

The seconds seemed to last forever, he says.

“Imagine if you put water in a balloon, and then threw the balloon into a swimming pool,” he says, explaining what the experience felt like. “And now you push all the walls of the swimming pool out in every direction. And now the pool is a small lake, and now it’s an ocean into infinity. And now you pop the balloon, so there’s no more membrane separating you from the ocean. But you still have a sense of I-am-ness. That’s a paradox you can’t make any sense of.“

He was diagnosed with sick sinus syndrome. His heart’s natural pacemaker doesn’t work properly. Since the diagnoses, he has had three artificial pacemakers and another flat-lining experience. It changed his mindset. He became keenly interested in the people around him.

“When the first pacemaker was put in, the doc said ‘You’ll become really curious about things,’” Fiorelli says. He found it that to be true.

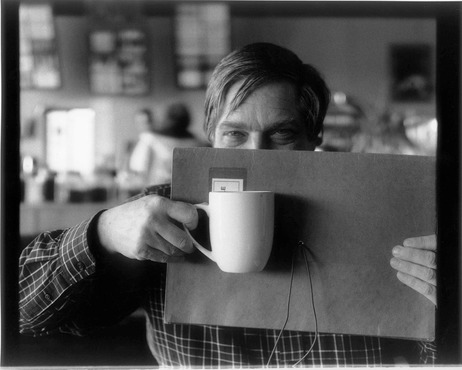

He struck up a friendship with Viktor Schreckengost, the industrial designer who was still teaching at CIA in his golden years. Fiorelli introduced himself to people around the building. And he drew and drew and drew. He drew people in meetings, assemblies and in other teachers’ classes. He still draws every day.

Some people assume the prolific drawing is part of his unconventional wiring, though Fiorelli dismisses that. “It’s not OCD, it’s not ritualistic,” he says. “Look, it’s an art school. If you have a problem with me drawing at an art school, you need to re-evaluate.”

In 2003, Fiorelli won CIA’s Viktor Schreckengost Award for teaching excellence. Nominations are made by students, faculty and alumni.

And in 2011, CIA gave him a one-man show of sketches he made during the first year of the college’s Digital Canvas Initiative. Incoming first-year students received iPads with instructions to use them in their artwork. Fiorelli, who eschewed email and was assumed by many to be a Luddite, took the lead.

“They gave me the iPad, and [a former administrator] said he thought I would hand it back,” Fiorelli recalls. Instead, he drew on it the first day and just kept drawing. “It became a sketchbook to me.”

As he looks toward the future, he sees work to do: drawings to be made, questions to be asked, experiences to be had — though he’s not yet sure exactly what kind. He plans to visit a lake that reminds him of his mother, who died a few years ago. He wants to be reminded of her in that setting, and to think about what it all means.

“What’s going to be weird is that I feed so much off what the students do,” he says. (Indeed, on his last critique of his teaching career, Fiorelli brought in his own answer to the assignment. It involved a plastic chicken and a ping-pong ball.)

In the meantime, the Fio stories will flourish. Countless are sweet. “Richard was my design guardian angel who didn't give up on me,” a former student writes on Facebook. “I am eternally grateful.”

And others are funny. Fiorelli has a favorite. This year, he heard 1997 grad Zack Petroc — a character designer who made his name working for Disney Studios — recount an entertaining legend of a Fiorelli fit from decades ago. Another student showed up at a critique one day with a lame design solution. The work had clearly taken no effort, but the student kept insisting he’d spent hours on it.

Fiorelli was furious and — in Petroc’s version — dropped an especially colorful four-letter word. The room allegedly fell silent.

To this day, Fiorelli has his own version of what happened, but prefers Petroc’s. It makes for a better story.

“Print the legend,” he says.

Latest Headlines view all

-

April 23, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art welcomes alum Omari Souza as 2024 Commencement speaker -

April 02, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art students partner with Progressive Art Collection to exhibit Ready, Set, Relay! -

March 04, 2024

Cleveland Institute of Art announces Curlee Raven Holton Inclusion Scholar Program

Questions?

For more information about this or other CIA news, contact us here.

Social Feed